by Vincent Moroz

INTRODUCTION

“So among the weapons of the staff, the pike is the most plain, most honourable and most noble of all the rest. Therefore among renowned knights and great lords this weapon is highly esteemed because it is as well void of deceit.” Giacomo DiGrassi, True Art of Defense, 1594

Wood-based weapons must rank as the oldest weapon form known to man excepting perhaps those made from stone. Inexpensive and simple to produce, their simplicity does not allude to their versatility or lethality. As a child I’d used deadwood found in the forest so I could fight and subdue the mighty animals found therein like the squirrel and woodchuck. It could be thrown, thrust and used as a club or force-multiplier. Made with readily available materials it was a natural thing to seek out when my only other weapon was a small pocketknife.

Who knows when humanoids began adding pointy bits to the ends of wood poles. Certainly as far back as we can remember in the cradle of civilization they have done so. In keeping with the best available technology people have sharpened the ends of wood poles, tied on stone and obsidian, and when metallurgy began to develop, metal tips of ever-increasing hardness were added to increase the penetrating capabilities of the older methods.

The spear was carried into almost every battle of recorded ancient history. Homer in his Illiad writes of the various heroes on both sides carrying the “long ash spear” as their primary weapon and how it was used variably for both throwing and thrusting. In describing the events that led to Hektor’s death, Troy’s hero is said to have thrown his spear at Achilleus, cursed that he only had one, and lamented that his death was upon him. Only then did he draw his sword and rush his foe before being killed by Achilleus’ spear. The extra reach and excellent penetrating ability of a spear tip would prove decisive in this encounter as it had with so many others in the famous battle before the walls of Troy.

From Corinth Museum. Photo by V. Moroz

For centuries Greek hoplites formed their famous phalanx as a near impenetrable wall of shields and spears, moving to their swords only when spears were broken or fighting distances directed as did the Spartans in the final phase of their battle at Thermopylae. Depicted in ancient writing and pottery, medieval paintings and tapestries, the staff supported and protected travelers while shepherds watched over their flocks with it. The soldier rested from his labour upon his spear.

There are archaeological indications that the barbarian Germanic tribes used fire-hardened oak spears and swords – ones without metal points or cutting edges – to fight the Romans and annihilate Varus’s legions in the Teutoburg forest during the rule of Augustus. Specimens of this type have been excavated that show notches from sword cuts but they are not cut through, indicating they were solid enough to fight against the metal blades of the day. Given the reach advantage that even a 6 foot spear would have over the short swords of the time this is not shocking to consider.

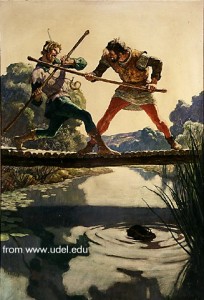

Popular legends, such as those of Robin Hood and his band of merry men (or Rocket Robin Hood with his amazing electro-quarterstaff) have firmly ingrained the quarterstaff into our collective English-speaking consciousness. Likely even in his day the reality would be that the staff was popular due to all the reasons set out above: low cost, readily available, versatile, lethal. In a day where hand-to-hand edged or blunt-force weapons were the common side-arm this was the perfect combination of traits. Even today, with knife injuries still out-numbering handgun injuries, a staff would be an excellent weapon for defense against knife and machete wielding attackers…although you might get a few looks getting on a bus or walking through the mall with a short-staff.

H.C. Holt comments on staff fatalities in Robin Hood’s own county:

“In the 103 cases of murder and manslaughter presented to the coroners of Nottinhamshire between 1485 and 1558 the staff figured in 53, usually as the sole fatal weapon. The sword, in contrast, accounted for only 9 victims and 1 accidental death.” 1

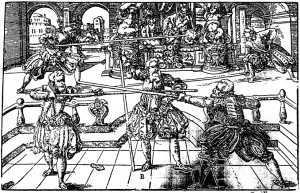

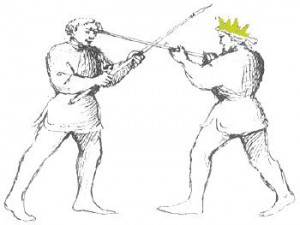

Meyer, Plate B

The staff has also been a symbol of authority from ancient on into medieval times where the Meister of a Fechtschule continued to use one in his official role of both school master and prize fight umpire. Undoubtedly this was the perfect weapon to separate men with sharp swords who’d gotten out of hand and were beginning to become overly aggressive during these events. George Silver, in his “Paradoxes of Defense”, describes how one person with a staff can beat two men with swords if he be skillful enough as the swordsman must always enter the dangerous space of the staff in order to attack.

It is not difficult to understand why the staff remained popular throughout the middle ages and beyond, with it’s flexibility and inexpensive cost, and with restrictions on citizens carrying weapons imposed at various times by various rulers, the staff would continue to offer citizens individual protection without fear of arrest. Although one wonders if this would have been the case were the stave shod with iron rings or points.

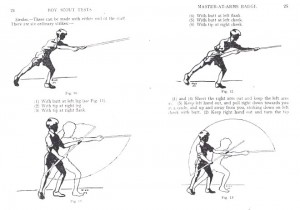

Staff fighting survived into the late 19th and early 20th century where prize fights in Victorian England were fought with the short staff in primarily half-staffing guards. The boyscout manual around the turn of the century had a staff fighting section for a Master-at-Arms badge. It is interesting how 100 years ago it was still considered proper to teach young men how to fight with potentially lethal weapons, whereas today fighting is viewed as bad, overly aggressive, something to be stopped in case someone gets hurt. The domestication of the western world is both fascinating and repulsive all at the same time. In any event, the half-staff techniques of both Victorian prize fights and the boy scouts are of interest despite being more geared to sport rather than combat as they illustrate standard techniques.

It could be argued that a staff and spear are two different weapons, but I might argue back that they would be held and used exactly the same way depending on whether or not one held a shield, and the only real difference is whether or not the ends have a point. Both weapons have the same shape and are the same length, each can be used to thrust, strike or throw and it really is only a matter of how many hands you have free as to how you may wield it. While fighting manuals do not survive from antiquity, the human body has changed little and the staff or spear not at all. Therefore it is reasonable to assume that how you can fight with a staff would be how you could fight with a spear at Plataea or in the Teutoburg forest. The biggest difference in modern times, besides your combination of offensive and defensive capability, would be in how you view the techniques: as a sport where everyone is supposed to survive unhurt, or for combat where you desire very quickly to kill or incapacitate your foe. I will admit that the staff is a more civilian weapon while the spear decidedly is military but even today there are some who will hunt the wild boar with a spear, bless their souls.

Pole-arms in general could be viewed as an extension of the staff/spear as they generally have a point for thrusting besides their other tools and edges. The biggest difference between staff/spear and pole-arm fighting would be the size, weight and intended use of the business end of a given pole-arm as compared to the staff. The weight of a halberd or bill head would make it less nimble than a staff or even a spear, however, their stopping power due to the mass of their head would give a pole-arm advantages unavailable in a staff or spear. While you’d have trouble pulling a mounted warrior off a horse by his harness with a spear, the English bill would do so quite nicely. You could thrust with a halberd but you will be hard pressed to chop deeply into anything with a staff. Similar weapons, all deriving from the common origin, but not the same.

DESCRIPTION AND CHARACTERISTICS

The size of the staff/spear has remained virtually unchanged since antiquity. A medieval short staff’s length was between 6 and 9 feet long, while a long staff was around 12 feet and the pike up to 18 feet. The former is equivalent to the length of a hoplite spear and the latter is the same as the sarissa carried by the Macedonian infantry of Great Alexander. The diameter of either staff or spear would be what fit comfortably in the palm of the hand, although it needs to be strong enough to handle the rigours of hand-to-hand fighting, with throwing spears being somewhat shorter and thinner. While this size may vary between individuals a diameter of about 1.5 inches for a fighting staff or spear would be useful for strength and the shaft itself must be made out of a suitable hardwood to endure the constant abuse it will be put through. Ash and oak were common.

The striking ends of a medieval staff may also have been shod with rings of metal, and some pictures clearly show short points attached to the tips. While these miniature spear points may not have been immediately lethal if they were shorter than three inches long, they would undoubtedly have created nasty puncture and slash wounds. One can imagine the extra striking force that iron rings would impart to a stave.

So what is meant by a quarterstaff? In his book “Broadsword and Singlestick”, 19th century master at arms, and expert with quarterstaff, Saber, and Singlestick, R.G.A.Winn, wrote the following description:

“The quarterstaff gets it’s name from the fact that it was gripped at the quarter-points, and the centre of the staff. With the left hand at the centre, ( palm upwards ) and the right hand at the lower quarterpoint, ( palm down ) This gives a three foot point end, and a very useful eighteen inch butt end. The grip was changed by releasing one hand only, and swinging the staff to catch it appropriately for the next technique or strike. “

This sounds like a short staff of about 6 feet in length although this grip would also work similarly with an 8 foot pole. What length is right for you? Silver tells us to stand our staff upright and reach the arm up as far as possible along the staff. After this measurement is taken add on additional length to comfortably hold the staff. For the average person this would make up to 8 or 9 feet long, but the real measure of a staff for any individual is your ability to handle it. Start with a 6 foot pole as a minimum and work up to a length that is usable and not bashing the ground with every movement. Personal suitability, rather than slavish adherence to textbook length, will help you be more effective with your training and fighting.

THE GUARDS

English, Italian and German traditions vary on what guards are important or included in their repertoire, but they also share common ground. In general three guards, or variations thereof, are found across the board or mentioned: a high guard where the butt of the pole is held over the head and the point angled to the ground, a low guard where the butt is held low to the side and the point is angled up, and, a near vertical guard where the butt is embedded in the earth and used as a deflective shield, sometimes with another secondary weapon in the other hand. The concept of half-staff guards also appears to be universal from either text or images.

Other guards are available and some will be discussed, emphasizing the German tradition almost exclusively, with input from Meyer, Egenolph and Gladiatoria, but also taking some input from Fiore de Liberi as he has a unique perspective on staff/spear fighting with his reverse guards.

Guard names are not common across the nations therefore I have chosen my own descriptions based on longsword guards. The reason for this is purely for ease of learning amongst longsword students and for no other reason. The name I use are Vom Tag, Ochs, Pflug, Olber, Nebenhut, Hengen, Half-Staff and Eisenport. Variations are included with the main guard where applicable. Subsequent practice of these guards has shown they are each useful in their own right and only need the correct situation to be effective.

In any event, do not look at what I present here as the final word on staff/spear guards or techniques, it is a beginning, a point of departure. This is my interpretation of what is demonstrated in the fighting manuals but this should never preclude you the scholler from using your own improvisation and adaptation to any system of fighting. I do recommend you try them all in sparring against various period weapons and in different sparring situations in order to make up your own mind as to what works for you and what does not. In the end, if you practice diligently, you’ll discover what is best for your strengths and body shape which is the beginning of true understanding and skill. Despite the rubbish we are spoon-fed, we are not all created equal, and therefore cannot fight exactly the same way. The German master, Joachim Meyer, says it best in his Fechtbuch of 1570: “Now since everyone thinks differently from everyone else, so he behaves differently in combat.” I often disparage many of his school-base techniques, but Meyer was no idiot. He was a Master of these period weapons in every sense and his broad knowledge is clearly demonstrated to those willing to read his Fechtbuch.

In English tradition the hand and leg should agree, which means whichever leg is forward, the same hand should be forward on the staff. Furthermore you should have the same leg/hand combination forward as your enemy in order to keep the fight on your inside and not towards your back or open side. The inside (your front between your arms) is easier to defend by moving the forward arm across the body to block, which is more natural and has a greater range of potential motion than movement backwards. In the English methods the legs are also kept fairly straight as the knees were viewed as targets. While this is indeed true, the German tradition does not support a straight-legged stance and I’d be inclined to follow this idea and keep my knees bent more like I was fighting with a sword or hand-to-hand. A lower center of gravity is rarely a bad thing and it just makes sense to have fighting stances follow common ground.

Keep in mind that guards, like weapons and armour, have a time and a place for use. Not all will be successful in every given situation as some require more space than others. Depending on where you came from in medieval Europe you would have handled your weapons differently or perhaps not even used certain weapons. The point I’m making is let the situation dictate the guard, the wrong answer is getting hit, the right answer is a successful attack/defense combination. The Masters tell us repeatedly to fight to the openings, they do not advocate dance step fighting.

Not all guards mentioned by the masters are clearly articulated or demonstrated in the original manuals, and one would assume this is for the same reason that Liechtenaur wrote in his verse style: one doesn’t want to give out all of one’s secrets! Practice will bring a light to your understanding, or as Hanko, the Priest, Doebringer says to us: “For practice is better than art, your exercise does well without the art, but the art is not much good without the exercise.”

Vom Tag:

Meyer, Plate G

Called the high guard by Meyer, he does not actually demonstrate it with a staff, just a halberd. The staff is held upright over the shoulder with one hand a few inches from the butt and the other hand higher supporting the weight of the staff. The picture does not show leg and hand agreeing, but this may be due to the transition Meyer envisioned with this guard. You can hold the guard with your hands in either position and should test how it works for yourself.

This guard threatens a powerful strike from above. In order to get the most power from an overhead strike as Meyer demonstrates you need to cock the staff back somewhat to get a larger range of motion and more force than simply striking from a raised position would provide.

That being said, if your leg and hand agree it has been demonstrated that a quick strike akin to the longsword “non-telegraphing” Scheitelhau does work suitably with a 6 foot stave. It is very fast and with good hardwood is much more damaging that merely dropping your arm from the stance in Meyer’s picture would be. There is also no reason you cannot strike a longsword-style Zwerchhau from Vom Tag although it does not move quite so quickly as the Scheitelhau.

You can transition easily from these strikes into other guards and it would seem the only thing you really cannot do from Vom Tag is thrust.

Olber:

This guard is again described by Meyer (as the low guard) but not demonstrated with a stave. Adopt Olber by having the leg and hand agree, holding the staff with the tip pointing low to the ground in front of you and the butt close to your hip in your rear hand. If you had a stave longer than 6 feet you would undoubtedly have more of a butt length than seen here in Meyer’s picture.

Meyer, Plate C

Olber, like its longsword cousin, gives the illusion of an opening but in doing so threatens either swift blocks or attack from underneath, including low attacks to the legs and thrusts under the chin. Winding up to a Hangen with the rear hand, or into a Pflug with the front hand (for displacement) is also possible. Like it’s cousin, this Olber is best used against one who is a Buffalo, not a Master.

Fiore shows this guard when begin attacked from behind with the response being a turn towards the enemy and a thrust into his face, the strike coming after a block of the enemy’s attack. If more space was required, one could turn away from an attacker as well as into him.

de Liberi: The Opening Play

de Liberi: The End Play

Gladiatoria, with ecranche, 7r

Gladiatoria demonstrates this as a spear guard being held with one hand and the other used to hold an ecranche, which is a small bucker-like shield with a notch used to support the spear while mounted. Here the spear is meant to be flipped up and thrown or thrust after defending.

Pflug:

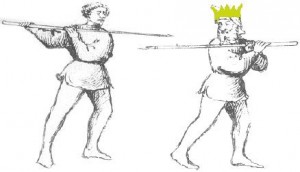

Gladiatoria, 6r

This is called the middle guard by Meyer and is demonstrated with both the staff and pike. In Gladiatoria this guard is shown with the spear and there is almost none of the angle one finds in the English version of the guard, which is there called the low guard. Hold the the staff with the rear hand close to the hips, and with the front hand, hold the tip up and pointing towards the enemy’s face. Ensure you can see over the tip of your staff. Swetnam and Meyer agree this is the preferred way to meet your opponent.

Pflug, like the longsword guard, is an all-round good position to meet many attacks, transitioning easily to other guards with windings, and for blocking or delivering thrusts from. If you hold the guard with rear hand lower, as per the English style ,it is an easier guard to support a heavy staff with. The more you threaten the thrust to the face or upper body, the more your opponent is likely to pay attention to your tip.

Ochs:

This guard is nicely demonstrated in the anonymous German Fechtbuch published by Christian Egenolf and in Gladiatoria. Fiore shows this guard held against attacks to the rear and many of his attacks start from here. Hold the staff beside the head with both hands, the shaft either level or pointing slightly down. The grip is demonstrated similar to that of the longsword guard and the lead hand can be thumb forward or reverse.

Gladiatoria, 3v

Ochs threatens thrusts or plunging thrusts to the head or upper torso. It also transitions quickly into Pflug or Hengen which show it to be a versatile guard and one well suited to feints.

de Liberi, Ochs defending rear

Nebenhut:

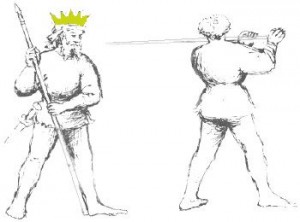

Meyer, Plate A

We see Nebenhut only in Meyer and the guard is so named by him. His description and drawing both demonstrate this guard with the body well cocked for maximum striking force but clearly with the forward side of the body open and unprotected. Unprotected, yes, but the speed at which you can unwind in Nebenhut is amazing. I might caution trying to hold this guard tightly wound for extended periods as it will be fatiguing.

Nebenhut threatens powerful horizontal strikes to any part of the body with either one hand or two, and transitions well into Hengen. Be careful not to confuse this guard with rear-Hengen as they are quite different.

Hengen:

Meyer, Plate A

Called the rudder guard by Meyer, this resembles the high guard from the English tradition. The butt of the staff is held high above the head by the rear hand and the tip hangs lower but does not rest on the ground. The forward hand supports the staff in such a manner that it can accept blows from a position of strength. This guard is best done with a staff that is not too long for you as the point can be close to the ground.

Hengen from Swetnam

Hengen protects the head and upper torso while blocking strikes to the lower limbs. It transitions easily to Ochs by pulling the hands parallel to the shoulders, and to Pflug by winding the rear hand down to the waist.

This guard can also be held to the rear for use in deflecting thrusts or thrown spears as demonstrated in Gladiatoria. Here the transition is from deflection to thrust from Pflug. Note that the body is not cocked as per Nebenhut, but squarely faces forward to the opponent.

Half-Staff:

Half-staffing is a technique for closer distances. Skill at half-staff is useful in dealing with enemies that are closing in quickly on you, or to get past the powerful distance strikes of another with a longer pole weapon. If worked with speed and aggression you can keep two at bay. Adopt this position by holding your hands equal distance from the ends at the center of the staff, being careful that your staff length is not so long that the tips hit the ground when striking. How the staff is positioned in relation to your body is a matter of personal preference and a matter of how you either prefer to defend or prefer to strike out from.

Egenolf

Meyer’s plates F and L demonstrate how this guard can be used to block powerful overhead strikes or trap and strip your enemy’s staff. See those fighting in the middle ground.

This guard threatens powerful strikes from either hand with great speed to any part of the body, but cannot do so from any distance. Effective blocking of strikes from above can be achieved, but as both your hands are now prominent targets, do not hold half-staffing in a static way for long. Use it while closing in and when the longer reach of your staff in other guards is no longer required or is a hindrance. Half-staffing can be used as a prelude to grappling.

Eisenport:

This guard is demonstrated in both Gladiatoria and The Flower of Battles. In both it is shown held in one hand using a secondary edged weapon in the other; de Liberi also shows this guard with no secondary weapon. Swetnam professes his dislike for it as it brings the fight too close to the body for his comfort.

Adopt Eisenport by holding the staff with one hand while resting the butt firmly on the ground. You can hold it perpendicular to the ground, or angle it towards yourself somewhat for greater deflection. If you have a secondary weapon available, hold it in your other hand and use the spear to guard and deflect strikes and thrusts from any weapon.

Gladiatoria, 5v – with secondary weapon

This guard gives the illusion of proximity, but if used in short controlled re-directions with good footwork, it is very difficult to get past. It can be used with a short sword or dagger as an offensive weapon, making the staff like holding a very large shield. If used without a secondary weapon, a two-handed grip allows short, quick strikes or thrusts to any part of your enemy, especially lower limbs.

There is also a modified version of this guard where the stave/spear is held with both hands and does not necessarily rest on the ground. The spear is held somewhat more in front of the body at an angle, almost like a very low Hengen. This particular guard is also seen in Filipo Vadi’s manual with spear, with the hands being held as seen here in Gladiatoria for spear and stave. Gladiatoria tell us that this is an important guard from which all other guards and techniques of the staff derive from.

Gladiatoria, 55v

Other Guards:

Other sword-like guards may also work, such as queen’s guard, but will take some experimentation. This may work better from half-staffing or with a shorter staff so it does not make contact with the ground during maneuver. Odd hand guards, where your foot and leg do not agree may work to exploit an opening, and any non-standard method of thrusting, including an approximation of a spear thrust, are all fair game if the opening is there. Imagination will begin to work with practice. One thing I do not advocate is throwing your staff or spear, unless you have some form of backup weapon, especially when fighting another staff man. Gladiatoria speaks to actions on losing your spear in the Lists.

FIGHTING TECHNIQUES

J. Christoph Amberger has this to say about the staff in his book on the history of the sword:

“Had fencing history indeed been one of linear Darwinist evolution, where the superior system survived, modern fencing tournaments would be fought with six-foot fiberglass shafts in a circular arena.” 2

There are a variety of techniques that can be used with a staff or spear depending on the attack available or the defense required. As always, these differ between the masters. What they all agree on is that you fight to the openings that are presented, which means, there is no one way to start and finish a fight with staff (or any other weapon for that matter), only what you see your enemy leave open to you in their stance or attack and how you choose to exploit it. But beware! Obvious openings may be there to lure you in for the kill, and the masters tell us this is another technique you need to remember to use yourself – feinting and deception.

Another common theme you’ll find in almost any type of fighting, and Swetnam is very clear about this in his staff section, is that you should not wait to be attacked, but instead attempt to gain and hold the initiative so that your enemy needs to react to you and cannot form a strategy of attack. If your enemy has the initiative, work to take it from them. This is a psychological attack as well as a physical one in that your enemy may be overwhelmed by your attack and lose heart for the fight, prompting a flight response. It is a victory like any other should your enemy run away. Be open to Ringen from staff work as in the end all fighting can be brought to hand-to-hand.

Changing Sides:

You may either want to change sides or need to change sides while fighting with a staff, which can be accomplished from many of the guards. To complete a change, either by moving forwards to thrust or by moving rearward to make space, do the following:

- loosen your grip with the forward hand so that the staff may pass through it easily

- with the rear hand, push the staff through the front hand until the two hands meet; fully extent the arms if possible for extra reach

- immediately let go with the rear hand while simultaneously pulling sharply backwards with the front hand

- the free hand catches the staff and now takes its place as the front hand when you step forwards or backwards

- the footwork you use will depend on whether or not you wish to move forward or backwards, but when all is said and done, you should end up in a proper guard

Swetnam advises us to change sides to gain advantages or to match our enemy’s stance.

Strikes:

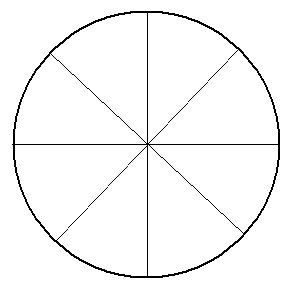

Any of the 8 strikes that can be performed with the sword can be completed with the staff or spear. Don’t get a fixed view in your head of the standard cut circle on the middle of the body, as Mittlehau to the head or the knees is just as valid as one to the torso. Neither should you forget Unterhau to the groin as, outside of sporting contests, this is a completely valid target. To complete a strike, do the following:

- slide the forward hand toward the forward tip of the stave while pulling to the rear with the rear hand

- firmly hold the forward hand in position and slide the staff through the rear hand while swinging the stave in which ever arc you wish to strike from. Step when striking. On any side you will have the options top, bottom, middle and angled up and down

- you can continue to perform as many strikes as desired, but when finished you should end up in a proper guard

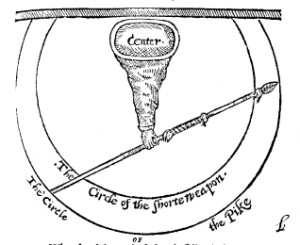

From a half-staff guard you should be able to strike or thrust with equal speed and ferocity towards any of the striking directions for a total of 9 options. Remember to use the power of your hips, especially from the half-staff, and cock the body somewhat while striking as is seen in Meyer’s Nebenhut guard. Striking with the arm alone will never generate the power potential generated using the whole body. We are also reminded about the speed of strikes by Giacomo DiGrassi, in his book “True Art of Defense”:

“Whereby it is manifest that the pike, the longer it is, it frameth the greater circle and consequently is more swift, and therefore maketh a greater passage. The like is to be understood of all other weapons, which the longer they are being moved by the arm, cause the greater edge blow and greater passage with the point.” 3

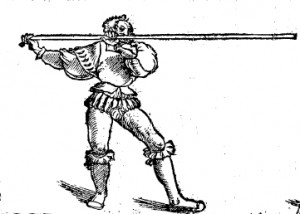

From DiGrassi

Just like a wheel moves faster on the outside than at the hub, so does the staff at is travels. Therefore strike with the few inches close to the tips for maximum force and damage, and not closer to the center where it will have little or no effect.

Thrusts:

Thrusting will deliver the full force and weight of a blow into a very small area, think of this like squeezing all the PSI out of your attack as possible. When thrusting you are making a more precise attack therefore look to attack sensitive areas like the groin, neck, ribs and face. None of these are overly spongy to absorb the impact. You can make quick thrusts at opportune targets without changing sides, or you can thrust as a part of a change in your stance. If using a spear think penetrating instead of blunt force trauma. Look for the softer areas so your attack is not stopped by bone. Thrusts can be made one or two-handed.

Defense Against Grabs:

It is always best not to position yourself where your opponent can grab your staff, however, this may not always be possible. Should an opponent get a hold of your staff, you can do a couple of things to recover it so long as you don’t panic and lose your balance. Seek instead to make your opponent lose their balance if you can. If your staff or spear is grabbed only by a hand you may be able to do one of the following:

- sharply pull it to the rear while stepping backwards.

- wind the staff in a large circle against the opponent’s thumb

- thrust sharply forward followed by a sharp rearward step

- throw the staff across their body and close to Ringen

Gladiatoria, 3r

If your weapon is trapped under his arm, you may have to abandon it and close quickly to wrestling. Don’t get focused on your weapon so intently that you allow him to steal your weapon and your initiative. In the picture below the defense against a spear thrust is to trap it under your arm and then throw the sword where ever it is best to throw. You are best not to allow your opponent a free throw.

Basic Principles:

The techniques here do not include every thrust or feint ever mentioned, nor do they include input from everyone who ever wrote a book on fighting once. They do convey ideas and concepts that you will then need to begin working with the staff, as no amount of reading about it will ever replace the hands on practice hours it truly takes to be masterful with anything. Techniques are in point form under the master’s name they were gleaned from, but my guard names are used exclusively. I have included input from the English masters for this section.

All the points from all the masters, even if they were all written faithfully in these pages would not make any of us a master ourselves. Take what is here and combine it with practice to understand what the masters teach. I doubt the masters were trying to give us all the possible combinations and permutations available in attack and defense, as no volume is so large as to be so complete. There is a list of books at the end of this work that I recommend you peruse if you are looking for more of “if he does this, then do that”. Each will contain something to help you on your way.

Swetnam:

- basic premise: block, counter-attack, return to guard.

- for high attacks, block with your staff and return a thrust, assume a proper guard as soon as possible.

- thrusts can be made with one hand.

- for low attacks, dip your point to the ground but do not pitch it in. These can also be dealt with by moving your leg out of the way or avoiding strikes with footwork.

- don’t over-carry your staff in defending, which is to say don’t move your staff farther than you must to counter an attack in case it is a feint and you cannot recover in time to meet the real attack.

- use false moves and feints when it is safe to do so.

- practice so you can use the staff equally well on both sides. If you cannot do this well, stay on your strong side and do the best you can.

- use Hengen in low-light conditions as it protects the head better. This is unless you have the longer staff and can keep your enemy at bay with it. In low-light you may wish to retreat and not engage. If you engage, seek to close quickly.

- Pflug is the best all-round guard, and is equally effective for short staff, long staff and pike.

- when closing with the staff, move to wrestling if you are good at it.

- do not thrust with one hand at a swordsman as you must return to your guard faster than when fighting another staff man.

Silver:

- a staff man strikes at the head and thrusts to the body if he is well skilled.

- if you first thrust, then follow up with a strike (or visa versa) especially if fighting against an edged weapon as a swordsman cannot defend both attacks one after another.

Meyer:

- basic premise: get ‘off-line’ and counter-strike, or, block and counter-strike.

- quarterstaff fighting is the basis of all other pole arms.

- most attacks are to the head, or to the head and another body part in combination.

- always return quickly to a guard after an attack is made.

- seek to bind an enemy’s staff and attack the openings from the bind.

- openings can be created by pushing off from the bind and striking either over or under his staff before he can recover.

- use quickness and deceit.

- when an enemy extends his staff out from himself, strike at it to knock it away and thrust at him before he can recover. Be careful not to lose control of your staff lest he recover before you do.

- when an enemy pushes hard against you in the bind in an effort to move you, go under his staff and strike it in the direction of his bind, then strike to his head before he can recover.

Meyer goes on to give us an additional number of paragraphs regarding the use of the halberd and the pike. Talhoffer has some spear in the Lists but more on the halberd which I’ve chosen not to address here even though it is related; he does not address the staff. Sutor’s work is obviously based on Meyer, as is indicated by his almost exact copies of Meyer’s drawings, therefore Sutor is not quoted.

In English tradition I’ve included a couple of points from Silver that are not covered by Swetnam, but neither Silver nor Wylde add anything significant to what Swetnam covers in his work. Most of Silver’s coverage of staff and pole arms is to tell us which are superior to which others. This is perhaps of more use to those already skilled with staff-based weapons and those who truly understand the differences in the fighting blades placed on said staff-based weapons.

Gladiatoria:

This anonymous German fighting manual from the early 1400’s demonstrates spear combat exclusively in armour. There are twelve techniques for the spear whereas there is only one page on staff fighting that shows two main guards by non-armoured combatants. All other staff guards are stated to derive from the two shown. The spear section of Gladiatoria is specific to fighting in the Lists, the Judicial Duel popular in medieval Germany, and so we must view the techniques in light of their intended use: single combat to the death in a controlled environment. The combatants have access to the ecranche and use it in many of the techniques shown, but not always. Many of the guards in this document are clearly demonstrated in Gladiatoria and spear throwing is discussed on many of its’ pages. All the combatants have a sword and a dagger in addition to the spear.

What is interesting about Gladiatoria is that the pictures are well detailed and contain descriptive text regarding the techniques drawn. Usually there is a technique with a counter on each page. The outcomes of many of the techniques is similar to Hans Talhoffer’s Fechtbucher as there is a bloody end apparent. While this book obviously had the judicial duel in mind, the techniques are still relevant to war or street combat although they do not cover the group skills required to fight in organized warfare. However, just as the modern soldier must learn to shoot and fight with his bayonet against a single opponent, the medieval warrior would need these skills prior to moving forward into war. They are all relevant as killing skills.

As an aside on the judicial duel, Hans Talhoffer in his Fechtbuch of 1459 lists a number of specific reasons to seek a one-on-one duel for satisfaction against a wrong which include such things as murder, treason and using either a maiden or a lady. I often wonder why they stopped the judicial duel as it likely made for a more polite society than our own, where criminals are routinely protected from the repercussions of their heinous actions. A revival of this old practice would not be out of order in our own times. For a list of offenses that constitute a reason for judicial duel read Fight Earnestly, which is an excellent translation of Talhoffer’s book by Jeffrey Hull.

Techniques in Gladiatoria include throwing the spear at available targets, which are never specified, but are merely stated along the lines of “where you see fit” or “where it will have best effect”. Much is assumed the fighters will already know. What is clear is that you should keep and work your spear for as long as possible while denying your opponent the use of his. If you lose your spear due to a poor throw or having it taken away from you, you are to work quickly to deflect any spear attacks from your opponent and then close to a closer range to bring other weapons to bear. The writers of this manual do not tell us how to work the spear, or where to throw it, so you must go back a step further to the other masters such as Hanko, the Priest, Doebringer, who tell you to fight to the nearest opening as it arises. Keep your fighting dynamic, seek the before and then the after as described by Doebringer, and do not give your opponent a chance to steal the initiative. This is the true way of the fight, never be a slave to the 1-2-3-4 dance steps of some techniques.

CONCLUSION

The humble staff and spear remain as perhaps most versatile hand delivered weapons of all time. Inexpensive to produce they are among the most lethal non-projectile weapons you can wield. In historical one-on-one encounters it has been proven to be superior over the sword, even though it has been eclipsed in favour by the sex appeal and status of the sword. If you could choose one ancient weapon to take with you anywhere, it should be the spear.

Let me remind you again that you’ll never get any good at anything (except reading) by reading about it. Make certain that you get up off the couch and get some quality time with your favorite pole arm if you hope to know it as the masters did. Strengthen your body so it can manage a prolonged bout without tiring, and be open to create adaptations and variations in your movement and style. True understanding comes not from slavish memorization of a fixed set of guards and dance steps, but from understanding the possibilities and reading the openings and weaknesses your enemy presents in the fight. From there you only need to train yourself to exploit them.

A final warning on the techniques found in this article. As I’ve mentioned they are killing skills, not sporting skills and you should practice them at your own risk with all due respect to the danger potential of a strike or thrust with a piece of hardwood. I recommend you exercise restraint when sparring with others, even if using padded weapons and wearing safety kit. Always seek instruction from a qualified WMA instructor in your learning.

SOURCES/RECOMMENDED READING

- Robin Hood, J.C. Holt, 1982 (1)

- The Secret History of the Sword, J. Christoph Amberger, 1998 (2)

- The Illiad, Homer

- The Flower of Battles, Fiore de Liberi, 1409 (translated by Hermes Michelini, KOWR, 2001)

- Gladiatoria, Unknown, 1400’s, (translated by Hugh T. Knight, Jr., 2008)

- Fight Earnestly, Talhoffer Thott 1459, (translated by Jeffrey Hull, 2007)

- The Art of Combat, Joachim Meyer,1570 (translated by Jeffrey L. Foreng, 2006)

- True Art of Defense, Giacomo DiGrassi, 1594 (3)

- Paradoxes of Defence, George Silver, 1599

- The Schoole of the Noble and Worthy Science of Defense, Joseph Swetnam, 1617

- English Master of Defense, Zach Wylde, 1711

- Quarterstaff, Sgt Thomas McCarthy, 1883

- Fighting With the Quarterstaff, David Lindholm, 2006